Today we’re going to talk about my favorite topic: how terrible John Muir was. I have given so many presentations on the racist origins of the American environmentalism movement (I’m actually going to go back on this sentence in a bit) that the name John Muir goes through my head with the same frequency and disdain that Joe Exotic says “Carole Baskin” in Tiger King. For those of you that do not know John Muir, he is credited as “the Father of the National Parks” and co-founder of the Sierra Club, a grassroots organization that today does really amazing environmental activism work. He is known for his work to promote the conservation of nature, which on the surface sounds all well and good, but if you dive a little deeper he becomes much more sinister because he promoted two very dangerous ideas: the concept of “pristine nature” and nature being a space for white city dwellers to escape to. It was on these ideas the national parks were founded and continue to operate today.

There is no “Pristine Nature”

This concept is very problematic- especially in the way Muir exploited it to promote the genocide of Native Americans. First of all, there is no such thing as pristine nature because all nature has been impacted by human activity, both historically and contemporarily. The pristine nature idea erases the relationship Indigenous people have had and continue to have with their traditional lands. It dismisses the fact that Indigenous people actively contributed to managing, caring for, and living off of the land in substantial ways prior to colonization. Reducing the relationship between Indigenous peoples and their traditional lands perpetuates stereotypes that have been used to justify the stealing of Indigenous lands.

The pristine nature idea also perpetuates the notion that there is no place for humans in nature. Western science tells us that human activity is generally bad for the planet, and that we can only destroy and pollute our ecosystems. Indigenous scholars and ways of knowing however tell quite a different story. There are ways to live sustainably, and even benefit the environment. For example, the Kayapo people indigenous to the Amazon planted many forested areas that were once thought to be naturally occurring, and these planted areas are even more biologically diverse than natural forests (Posey, 1985). Indigenous perspectives are critical to conservation but unfortunately they are often excluded.

Some quick facts:

80% of the world’s biodiversity is on Indigenous land. Indigenous lands also experience far lower rates of deforestation compared to lands that have been taken from Indigenous peoples.

The Whiteness of Environmentalism

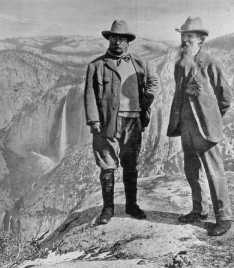

Muir took advantage of the pristine nature idea to displace California tribes (Miwuk and Paiute) from their ancestral lands in order to establish Yosemite because he viewed the preservation of nature and human activity as incompatible. This model was then replicated across the country to establish the national park system we have today, displacing dozens of tribal communities. Muir intentionally advocated for the displacement and eradication of Native Americans; he was racist and is quoted to have said many atrocious things about the Indigenous people of North America. It is wrong to try to view him in any positive light or give him the “benefit of the doubt”… this man was unequivocally horrible.

Muir’s “pristine nature” national park model led to the national parks being solely devoted to nature and devoid of the original inhabitants that managed the land for generations. The legacy of this is that outdoor spaces and environmentalism are overwhelmingly white. For more information refer to my previous post: https://learninghowtoscience.com/2020/06/18/in-solidarity-with-black-lives-matter/.

The problem is it is not just Muir. So many white leaders of the environmentalism movement that we view as heroes were actually really bad people. Muir, Roosevelt, Leopold, and many more were praised in my conservation biology and environmental science courses for their progressive policies and ideas. It wasn’t until much later I educated myself on the darker side of the environmentalism movement and began to speak out against it.

Moving Beyond Muir

As promised I am going to contradict my own statement from the beginning of this post about the origins of American environmentalism being racist. While yes, it was for the most part, Muir had a contemporary that was extremely influential in environmentalism and sustainable agriculture—George Washington Carver. What is taught about Carver’s legacy in schools is usually restricted to his work inventing peanut products, but he also was responsible for promoting the use of crop rotations to reduce the depletion of nutrients from the soil. I thought it would be best to end this post by highlighting the work of Carver since he is someone that is not typically included in conversations about environmentalism, but deserves the recognition that is given to non-BIPOC environmentalists. His story, as well as many other Black and Indigenous peoples’, needs to be told and promoted in the same way white environmentalists are in mainstream media. We must all strive to recognize and celebrate the contributions of Black and Indigenous peoples in environmentalism and environmental science, and make environmentalism more inclusive moving forward. I will be speaking on this subject more in later posts, but for now thanks for reading!

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ea/5f/ea5f84ad-fd2b-4a0a-8172-0c96dc65bee7/gettyimages-515176998.jpg)

Definitions:

Biodiversity- the variety of life on Earth or in a specific ecosystem

Environmentalism- social movement concerned with protecting the environment

Colonization- a process in which people settle in an area and take control of the land, resources, and Indigenous people. Colonization is a violent and ongoing process.

Works Cited:

Posey, Darrell Addison. 1985. “Indigenous Management of Tropical Forest Ecosystems: the Case of the Kayapo Indians of the Brazilian Amazon.” Agroforestry Systems 3: 139-158.